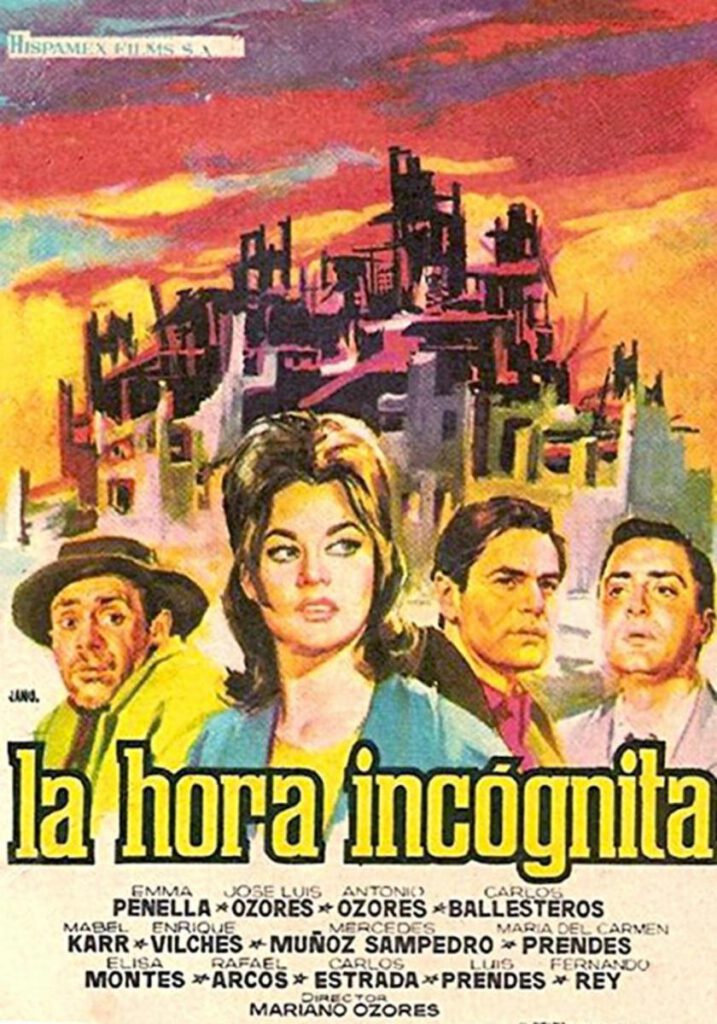

Review: La Hora Incógnita (1963)

by Elena Romea (*)

Mariano Ozores’ LA HORA INCÓGNITA (1963) occupies a singular place within Spanish cinema of the early 1960s. Better known for his prolific contributions to comedy and commercial genre films, Ozores departs from his familiar terrain to craft a speculative drama combining dystopian allegory with philosophical reflection. Made during a time of rigid censorship under Francisco Franco’s dictatorship, the film is notable not only for its genre (science fiction being a rarity in Spanish cinema at the time) but for its capacity to engage with contemporary political and ethical concerns through a veiled, metaphorical lens. Born in 1926 in Madrid, Ozores came from a prominent family of performers and filmmakers—his brother, Antonio Ozores, was a prolific comic actor, and his father, Mariano Ozores Sr., was a well-known stage actor. However, Mariano Ozores would go on to direct over 90 films, many of them comedies of manners or erotic farces known as españoladas. In some retrospectives, it has been suggested that Ozores himself did not feel especially attached to the film in later years, perhaps because it didn’t find the same audience success as his later commercial hits.

The film was produced by Aconito Films, a small production company known for producing films primarily in the 1960s and 1970s in Spain and distributed during a time when science fiction was not a particularly common or commercially successful genre in Spain. The musical was composed by Benito Lauret.

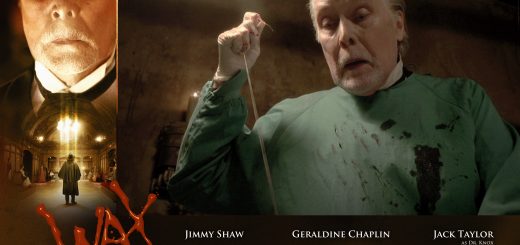

The cast features several well-known Spanish actors from the time, many of whom were already established in film, theatre, and television. Antonio Ozores, the director’s brother, has an important role in the film. Unlike the comedic and exaggerated characters he would later become famous for, here he gives a much more serious and low-key performance that adds a quiet touch of irony and sadness to the story. Another major name in Spanish cinema, José Luis López Vázquez, also appears. Famous for playing everyday characters in unusual or tense situations, he brings a lot of depth and subtle emotion to his role. Other performances come from Jesús Puente, María Isbert, and Antonio Casas. Puente, who often played figures of authority, takes on the role of a military officer with calm seriousness. María Isbert, daughter of the legendary actor José Isbert, gives her character a real emotional presence, and Antonio Casas, a familiar face in Spanish films. Together, this group of actors represents a wide range of Spanish society, helping the film explore big moral and social questions in a personal and universal way. Many of the main roles were filled by the same extended family members. Director Mariano Ozores worked alongside his brothers, actors José Luis Ozores and Antonio Ozores. Antonio’s wife at the time, Elisa Montes, was also part of the cast, as was her sister, Emma Penella. Rafael Arcos, meanwhile, was Mariano Ozores’ brother-in-law. In addition, Mabel Karr and Fernando Rey, who appear in the film, were married in real life, and Mari Carmen Prendes shared the screen with her brother, Luis Prendes.

Set in an unnamed town, considered Spanish, that has been mysteriously evacuated, the film opens with long takes of empty streets and deserted buildings. Soon, a small group of individuals is brought into this strange setting: a military officer, a civil servant, a prostitute, a priest, a scientist, a journalist, and a few others. None of them knows why they have been brought together, but all are informed they must remain in the town until “la hora incógnita” aka “The Unknown Hour” or “The Uncharted Hour” arrives—a vague yet ominous concept that remains unexplained until the film’s conclusion.

While the film’s structure borrows elements from ensemble morality plays and post-apocalyptic fiction, LA HORA INCÓGNITA is best understood as an allegorical narrative in the tradition of mid-century existential cinema. Each character embodies a distinct ideological or social archetype.

In this regard, the film may work on multiple levels. On the surface, it reflects the pervasive Cold War anxiety shared by many European nations during the early 1960s—a period marked by the Cuban Missile Crisis and the escalating arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union. The film’s most poignant commentary perhaps lies in its depiction of the prostitute, who, marginalized by society, emerges as the most emotionally lucid and ethically consistent character.

The title itself, LA HORA INCÓGNITA, serves as a metaphor for both nuclear apocalypse and personal judgment. It recalls Christian eschatology (“you know not the day nor the hour”) while also evoking secular existentialist motifs of dread and freedom. The ambiguity surrounding the nature of the final event allows the film to explore the possibility that the threat is less external than internal: a crisis of conscience, a spiritual reckoning, or the symbolic death of a morally bankrupt society.

Ozores’ use of black-and-white cinematography is said to contribute significantly to the film’s tone. The stark contrasts and careful use of shadow reinforce the sense of isolation and unreality, while the emptiness of the town amplifies the themes of alienation and silence. In terms of mise-en-scène, the film recalls the aesthetics of European modernist cinema more than it does the mainstream Spanish cinema of the time. The deserted setting functions not just as a physical space but as a metaphysical arena in which characters confront their own irrelevance, anxieties, and ethical failures.

That the film was produced under Franco’s censorship regime is particularly significant. The regime generally discouraged speculative fiction, which was deemed either frivolous or ideologically subversive. Yet Ozores cleverly blocks his critique in abstraction, avoiding explicit references to political realities while nevertheless exposing their psychological and moral consequences. The characters’ confinement, surveillance, and lack of agency evoke a stifling environment that would have resonated with audiences living under or being familiar with a dictatorial regime.

The performances are competent if occasionally theatrical, a common trait in Spanish cinema of the period. However, the strength of the film lies not in any single actor’s delivery but in the interactions between the characters. Their shifting alliances, philosophical debates, and moral confrontations serve as the real engine of the narrative. Dialogue occasionally veers into didacticism, but this is something a movie made in Spain in those years must include.

In the end, LA HORA INCÓGNITA is a surprising and thought-provoking film that stands out from what you’d expect from Mariano Ozores, especially if you know him for his later comedies. It might not have big special effects or fast-paced action, but its quiet, eerie atmosphere and philosophical edge leave a lasting impression. With a strong cast and a clever use of limited resources, the film manages to say a lot about fear, authority, and human nature without ever spelling it all out. It’s a hidden gem of Spanish cinema—strange, reflective, and well worth watching, especially if you’re into stories that leave you thinking long after the credits roll.

Here you have our special in Spanish about this film

__________________________________________________________

Elena Romea is the woman in charge of SPANISHFEAR.COM, Horror Rises from Spain and Un Fan de Paul Naschy . A literature and cinema researcher, Ph.D. in Spanish studies with a thesis about the mystic filmmaker José Val del Omar. She has published in different media and books such as Fangoria and Hidden Horror. She has also been in charge of several translations including Javier Trujillo’s complete works, La Mano Film Fest, The Man who Saw Frankenstein Cry, and many more.