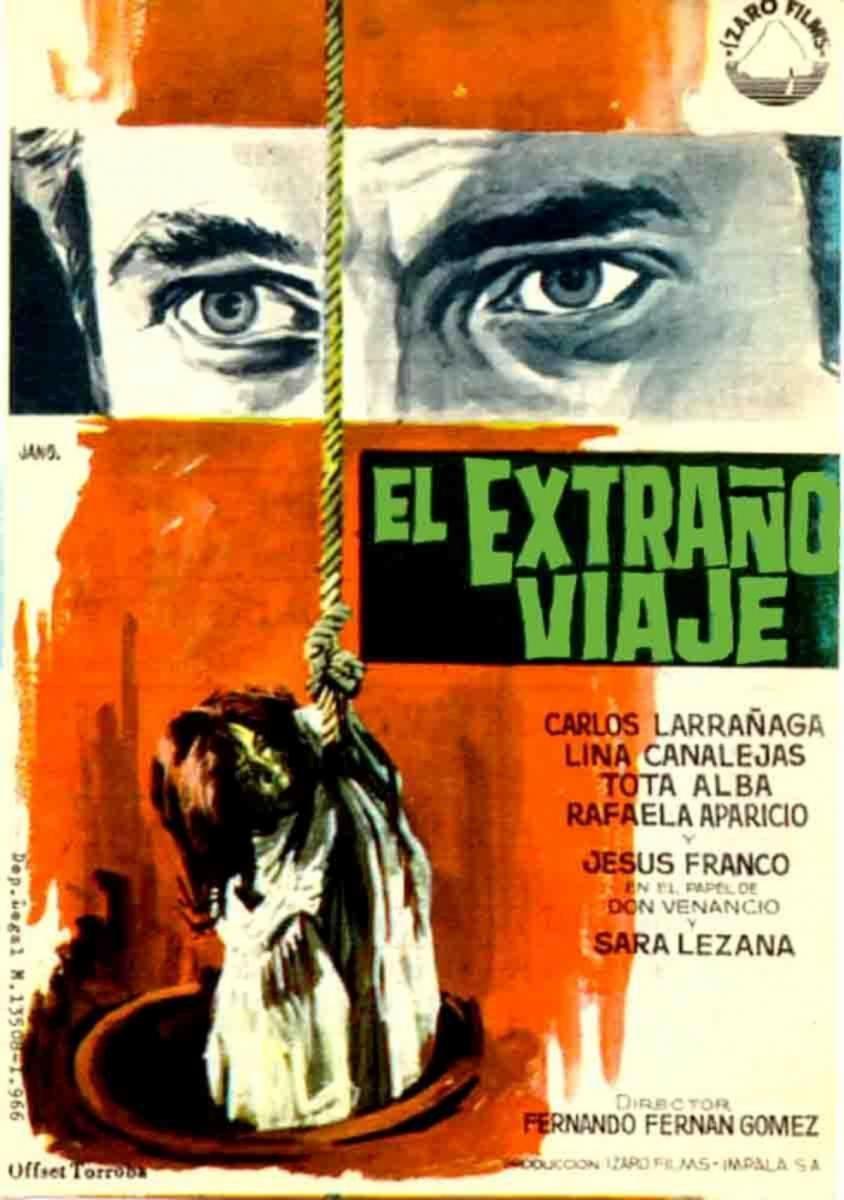

REVIEW: EL EXTRAÑO VIAJE (1964)

Directed by Fernando Fernán Gómez, tells a disturbing story—it shows the atmosphere of Spain under late Francoism, when the country was changing on the surface while remaining deeply repressed underneath.

By the early 60s, Spain was going through what the regime liked to call apertura. Tourism was booming, the coast was filling with dance halls and summer visitors, and the image of a modern, happy country was being carefully exported abroad. But inside, moral control, social surveillance, and fear of deviation were still very much alive.

Fernán Gómez, already an important figure as an actor, writer, and cultural troublemaker, directs the film. He knew this world: the small towns, the hypocrisy, the way authority was exercised not just by institutions but by families, neighbors, and “what people might say.” The script was co-written with Pedro Beltrán and inspired by a real crime. The true event is commonly known as the crimen de Mazarrón or sometimes the “crime of the three cups.” It happened back in January 1956 near the tiny coastal area of Mazarrón, in Murcia. A local fisherman walking along Playa de Nares came across a genuinely strange scene: two bodies—a man and a woman—lying dead on the sand, with three drinking glasses nearby. Two of the cups contained traces of poison, and a letter was found suggesting the couple had planned a “journey without return.” There was no explanation for the third cup.To this day, the exact truth was never known. Some theories were considerd: murder, suicide, or even a pact. Luis García Berlanga picked up on that story and planted it like a seed of uncanny possibility. With writers Pedro Beltrán and Manuel Ruiz Castillo, he turned the crime into a screenplay that transforms the fear of small‑town life into something deeper for Spain and its repression.

The coastal town where the film takes place looks like a Spain where everyone watches everyone else, where difference is suspicious, and where nothing truly private exists. At the center of the story is the trio of siblings: Ignacia, Paquita, and Venancio. Their home is a miniature dictatorship, and Rafaela Aparicio’s Ignacia is its supreme ruler. Aparicio, often remembered for warm or comic roles, has a disturbing performances. Ignacia doesn’t need overt violence; her power is bureaucratic, routine, absolute. She controls money, movement, time, and desire.

Lina Canalejas and Carlos Larrañaga play the younger siblings as adults frozen in a state of emotional immaturity. They are not heroic victims; they are damaged, resentful, and slowly corroded by years of humiliation. This is crucial to the film’s moral universe: El extraño viaje is not interested in innocence. It’s interested in what repression does to people over time.

One of the film’s most brilliant moves is how long it refuses to reveal its true nature. For much of its runtime, it feels almost like a dark costumbrista comedy. Scenes repeat, routines dominate, and nothing seems to move forward. Then, when the narrative fracture finally arrives, the shock doesn’t come from the act itself, but from the realization that it could only ever end this way. In a society where change is impossible, violence becomes the only form of movement.

Formally, Fernán Gómez opts for restraint. The camera observes rather than judges, allowing the discomfort to grow naturally. The music—often cheerful, even festive—clashes cruelly with what we know is happening underneath. The sea, traditionally a symbol of escape, becomes a hiding place. Nothing cleanses. Nothing redeems.

Here you can watch our special on the movie in Spanish