BRIEF INTRO TO SPANISH HORROR IN 1960-64/65

Matt Blake author of the book SPANISH CULT CINEMA introduces us to Spanish horror in the first half of the 60s.

The early 1960s was a period of massive transformation for Spanish Cinema. Previously, the industry had been primarily inward focused: the intended audiences for films were either domestic or the Spanish-speaking Americas. Films tended to be financed by Spanish companies, feature Spanish (or adoptive Spanish) stars, and receive minimal distribution across Europe or English-speaking territories. As such, the subjects tended to be of a type which appealed to these types of audiences, with the preference being for melodramas, comedies, and cine negro (urban thrillers, a fascinating genre which became established during the 1950s). Also, the style: most films were theatrical in nature, featuring relatively static cinematography and deliberate pacing.

This began to change during the first half of the 1960s, for several reasons. Firstly, contemporary foreign films became more commonly shown on Spanish screens, introducing budding filmmakers to novel cinematic techniques, whether drawn from Hollywood panache or new wave experimentalism. A few productions experienced a comparative success on the international market, including Juan Antonio Bardem’s Muerte de un ciclista (Death of a Cyclist, 55) and Berlanga’s Bienvenido, Mister Marshall! (Welcome Mr. Marshall, 53), which made people aware of the potential benefits of widening distribution areas. And the Spanish government introduced assorted financial changes to encourage film production in the country, not least increased subsidies for foreign co-productions. As a result, not only did the content of Spanish films begin to change, reflecting genres that were prevalent elsewhere in the world, but also the style: editing became tighter, colour photography became predominant, dialogue was reduced, and visual language was given more emphasis.

It’s no surprise, therefore, that it was a period that saw the release of several peculiar and idiosyncratic films, and here’s a very brief survey of some of my very favourite horror style productions from the period. Some of these films you’ll have heard of – most you probably won’t; many of them, unfortunately, aren’t available in English language. Almost none of them are strictly horror, although they do include horrific elements. [plug alert] For more information on them (and many other films besides), please check out my book Spanish Cult Cinema, Volume 1, 1960-1964 [plug over]. Anyway, here goes…

… But, firstly, let’s talk about the elephant in the room, let’s talk about Jesus. Jesús Franco, that is. This was the period during which everyone’s favourite purveyor of Spanish cult cinema was beginning to make a name for himself and, most importantly, when he was still firmly part of the industry (as opposed to a rootless auteur who would make films – or, some would argue, the same film over and over again – wherever he could rustle up a few dollars). During the early 1960s, he was seen as a promising and talented filmmaker, even by the mainstream critics (and even though his work was frequently in the ‘unpromising’ horror field). His first genre film Gritos en la noche (The Awful Dr. Orloff, 61), is generally considered to be the first contemporary Spanish horror film and it was undoubtedly influential, beginning a trickle of similarly minded productions. But it was still part of a general direction of travel that was occurring in Spanish cinema at the time: it was influenced by films that weren’t traditionally Spanish, it was part-financed by a foreign country (France) and it was distributed across Europe. All of which were factors which could equally be applied to the works of Spaghetti Western pioneer Joaquín Luis Romero Marchent. It borrowed elements of surgical horror from Georges Franju’s Les yeux sans visage (60), a lot of the style from Hammer, and elements of detective plot from the cine negro. It proved to be a heady mix and was far more successful than anyone anticipated.

But I’m not going to talk much about The Awful Dr. Orloff because (a) it’s been discussed in considerable detail elsewhere and (b) I don’t think it’s a particularly good film, sluggish, unfocused, and stodgy, despite some moments of visual flair. Far more interesting were his follow ups, which took similar material but knitted it together in a much more effective manner. La mano de un hombre muerto (63), a curious gothic giallo in which the young women of an isolated village are being picked off by a potentially spectral killer, is much better. The habitual Franco failings (wayward pacing, inane humour, a tendency to get distracted by pointless plot diversions) are kept to a minimum, while the habitual Franco positives (a keen visual sense, generally free-wheeling attitude) are more in evidence. The same is true of El secreto del Dr. Orloff (64), Franco’s much less discussed but superior sequel to The Awful Dr. Orloff, in which Orloff, naturally enough, doesn’t even appear. This time the villain is a camp chap called Dr. Conrad Jeckyll (or, in some prints, Dr. Conrad Fisherman, a name that literally drips evil), who has zombified his brother and is using him to – stop me if you’ve heard this before – murder assorted young women in the nearby village.

If you want some prime weird-shit Franco, though, I’d point you in the direction of El extraño viaje (64). This was directed by Fernando Fernán Gómez, a much-respected actor and filmmaker, who was working with a concept dreamt up by Luis García Berlanga. Franco this time is the star, one of a pair of slightly backward siblings who murder their more responsible sister… or do they. It sounds standard enough, but to get an idea of its innate oddness consider this: Franco was originally contracted to play the mentally challenged sister and only switched to the male role because Rafaela Aparicio was available whereas nobody was on hand to play the brother.

A lot of Franco’s films of the time touched on what’s known as the surgical horror genre. The same is true of the quite dismal La cara del terror (Face of Terror, 62), in which a woman who has been driven mad by her facial scarring bluffs herself into being the guinea pig for an experimental treatment by kindly surgeon Fernando Rey. The successful effects, though, prove to be only temporary, driving her into an even more dangerous level of psychosis. It’s a dull affair that makes The Awful Dr. Orloff look like a masterpiece by comparison.

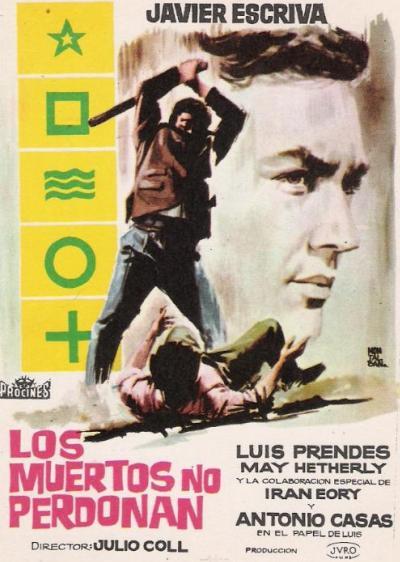

Another director who frequently dealt with surgical horror themes was the criminally under-rated Julio Coll. Although little known in the English-speaking world, Coll had a considerable reputation in Spain, and judging by his bizarre thriller Los cuervos (61) it was well deserved. The film is essentially a social satire, about a ruthless businessman (played by George Rigaud) who, after suffering a stroke, finds out who his true friends are, i.e., approximately nobody. As soon as people hear about his illness they start battling over his company, his money, and his power. The film then takes a stranger path when he meets up with an experimental surgeon (Paco Morán), who believes he can cure him… if he’s able to find a suitable heart donor. Los muertos no perdonan (63) plays a similar spin on the cine negro format, bringing in elements of parapsychology as Javier Escrivá – who has apparently been murdered while trying to uncover the truth behind his explorer father’s death – haunts the guilty men from beyond the grave. Coll also made the better-known Fuego, which did reasonable business when released in America as Pyro. This features Barry Sullivan as a scientist who is driven mad after his entire family his murdered in an arson attack; pausing only to come up with a new form of artificial skin – which he uses to cover his hideously scarred face – he sets about having revenge on the person who started the fire (and a lot of other random unfortunates as well).

Fuego was produced by ex-pat American Sidney W. Pink, who made a considerable number of films in Spain through the 1960s, releasing them to cinemas in Europe and direct to TV in the USA. Pink also produced one of the best horror films of the period, La llamada (aka The Sweet Sound of Death, 65), directed by Javier Setó. It’s a slow, moody affair, a surprisingly subtle meditation upon grief, about a young man who is haunted by the ghost of his ex-fiancée, who has died in a plane crash. Hoping to understand the strange phenomena he’s experiencing, he travels to the girl’s home in France, meeting his prospective in-laws. But they’re ghosts too, and everyone wants him to join them.

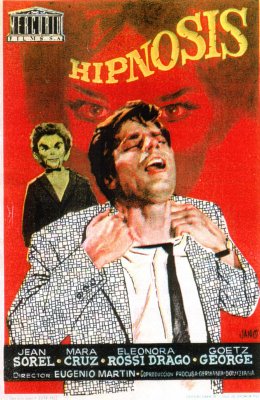

Often mistaken for a horror film, but in reality a slightly odd cine negro, Eugenio Martín’s Hipnosis (62) is another one worth catching. This features giallo favourite Jean Sorel as a young man who murders his hypnotist mentor (Massimo Serato) and is subsequently haunted by the dead man’s ventriloquist’s dummy. Naturally enough, everything spins out of control and the whole thing is made a lot more frightening by the fact that the demonic dolly is a dead ringer for ex-British prime minister Tony Blair. Hipnosis was a co-production with Germany (the influence of the Krimi films is visible) and Italy, and there were other international co-productions in the horror field with some type of Spanish involvement: Horror (The Blancheville Monster, 63) was a gothic horror in the Mario Bava style by Italian filmmaker Alberto De Martino, who worked frequently in Spain at the time; La maldición de los Karnstein (The Crypt of Horror, 64) was made by Camillo Mastrocinque with some Spanish investment but shot mainly in Italy.

And that’s just about it for this round-up of horror films made in Spain in the first half of the 1960s; a time in which the genre was very much an outlier, but with roots that were gradually becoming established. A final word, though, about some titles from other, connected genres. Fantasy films were experiencing something of a minor boom, thanks largely to comic titles in which religious or fictional characters arrive in Spain to sort out crazy human problems. The trend began with El día de los enamorados (59), in which Jorge Rigaud’s St. Valentine turns up to resolve some tricky romantic situations; it was popular enough to spawn a sequel, Vuelve San Valentín (62), again starring Rigaud. Then there was José María Elorrieta’s Mi adorable esclava (61), which featured Ethel Rojo as a mischievous (and sexy) genie, anticipating I Dream of Jeannie by a few years; while the devil himself turned up in La barca sin Pescador (64), as played by the reliably sinister horror favourite Julián Ugarte. I also feel duty bound to mention a largely forgotten film called La hora incognita (63), an On the Beach style tale about assorted characters marooned in a city which is about to be destroyed in a nuclear explosion; this was directed by comedy specialist Mariano Ozores, but it’s a deadly serious, sombre and rather effective attempt at science fiction (a genre which was even rarer in Spain at the time than the horror film).

_________________________________________________________________________________

Matt Blake has been writing about cult European cinema since the heyday of the fanzine in the 1990s. After editing a few issues of the short-lived, much lamented The Cheeseplant he released his first book, The EuroSpy Guide, co-written with David Deal, in 2004. More books have followed: Fantastikal Diabolikal Supermen, Giorgio Ardisson: The Italian James Bond, In the Name of the Law and Science Fiction, Italian Style. When not distracted an otherwise long-forgotten film he can usually be found wandering around the countryside near his home in Lewes or listening to discordant electronic music.